Bennettazhia

In 1928 paleontologist Charles Gilmore described and named Pteranodon oregonensis, a new pterosaur species based on a humerus and two vertebrae. It was discovered in rocks of the Lower Cretaceous marine Hudspeth Formation in eastern Oregon, USA. Gilmore had doubts that it actually belonged in the genus Pteranodon, but placed it there since it was most similar to Pteranodon among American pterosaurs known at that time. In a 1989 review of Pteranodon anatomy Chris Bennett noted that Pt. oregonensis was definitely not part of that genus, but was probably an azhdarchid instead. In 1991 Lev Nesov gave it a new genus name, Bennettazhia, named after both Bennett and purported relative Azhdarcho.

The humerus is uncrushed and well preserved, showing that the thin-walled bones were extremely strong, and helped show that pterosaur bones could handle the stresses of quad launching. The humerus is missing small portions near the elbow, as well as most of the deltopectoral crest. The deltopectoral crest is a ridge on the front side of the humerus found in many reptiles including pterosaurs that anchored the deltoid and pectoral muscles to the arm. In pterosaurs, the deltopectoral crest can be shaped like a rectangular blade, making the whole humerus look like a hatchet. Although most of the deltopectoral crest in Bennettazhia is missing, the base remains and shows that it was parallel to the long-axis of the humerus.

This is quite unlike what’s seen in Pteranodon, whose deltopectoral crest has a base that is twisted with respect to the long-axis of the humerus. This twisting was unknown to Gilmore when he named the species, as almost all Pteranodon specimens are completely flattened, and undistorted specimens were unknown at the time.

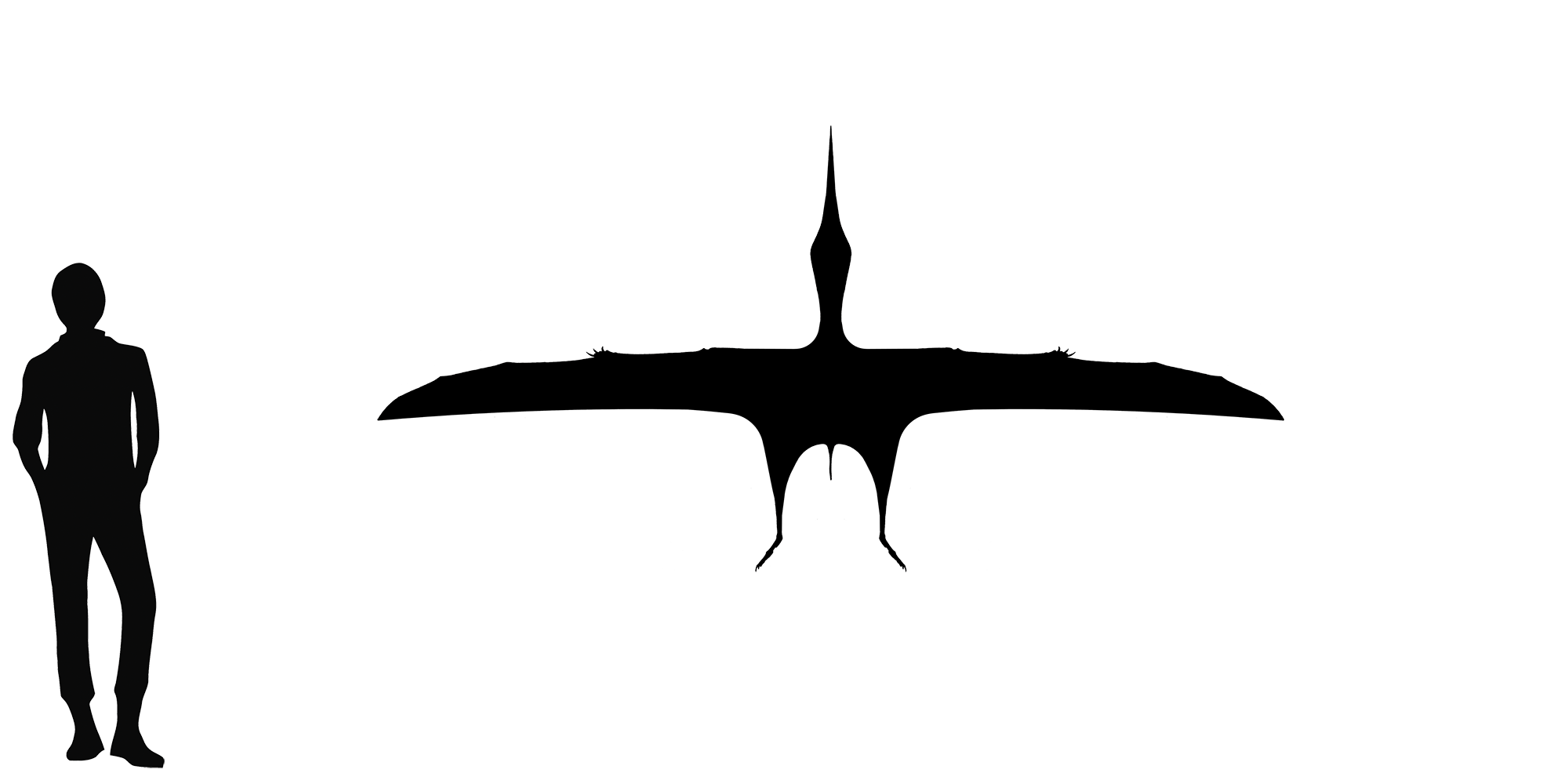

The humerus is about 18 cm long, and comparison to other pterosaurs tells us that its wingspan would be about 3.5-4.0 m (11.5-13 feet). The two vertebrae are from the back, and are fused together, possibly forming part of the notarium, the name given to fused vertebrae that help strengthen the torso of flying animals.

Although Bennett initially considered Bennettazhia to be an azhdarchid, hence the genus name, he later considered it more similar to dsungaripterids instead. More recently, paleontologist Mark Witton considered it to be an azhdarchid, but Brian Andres found Bennettazhia to be a tapejarid. Azhdarchids, dsungaripterids, and tapejarids are all part of a larger lineage called the azhdarchoids. Azhdarchoids were common around the world in the Cretaceous, and all had large skulls with over-sized nasoantorbital fenestrae, robust forelimbs, and long legs. For the illustration in this entry, Bennettazhia is restored as a generalized azhdarchoid.

The Hudspeth Formation was laid down between 110-100 million years ago under a shallow sea between the subduction zone to the west and a volcanic mountain range to the east, a feature that’s known as a forearc basin. This basin is the equivalent to the modern Willamette Valley and Puget Sound, but the associated volcanoes were much further to the east than the Cascades are today. Since Bennettazhia is only known from a humerus and vertebrae, it’s impossible to say anything about its diet with certainty. Most azhdarchoids were terrestrial predators, but tapejarids are thought to have also eaten fruit and nuts, and dsungaripterids probably ate shellfish. Being found in marine sediments suggests that Bennettazhia may have eaten fish.

Geological Age

Early Cretaceous

4 m (13 ft)