First classified as a member of the genus Pterodactylus in 1855, just like all other pterosaurs were during the 19th Century, Cycnorhamphus was reclassified by Harry Govier Seeley in 1870.

However, it was even made a synonym with the contemporary genus Gallodactylus in 1974. What is known though, is that Cycnorhamphus suevicus, the only species in its genus, was a member of the Gallodactylidae. The gallodactylids are related to the comb-toothed ctenochasmatids.

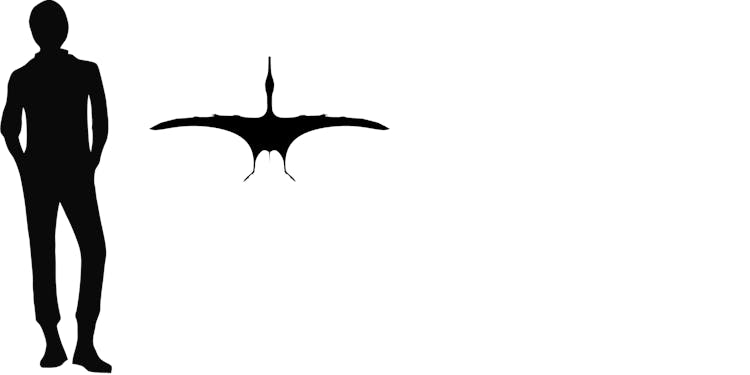

Cycnorhamphus is one of many Solnhofen pterosaurs, living during the same time and place as creatures like the well-known Pterodactylus and Rhamphorhynchus. Unlike these though, and the other pterosaurs present, it might have been eating tougher prey, a process that created a lot of tooth wear. Cycnorhamphus was certainly dealing with a lot of gritty food. Shellfish might be a possibility but for now any details about its diet are pure speculation.

Its jaws were certainly not the standard for pterosaurs, with a highly twisted and curved lower jaw and peg-like teeth at the front of the mouth. Many workers have assumed that this was a deformed specimen and that its jaws were just standard pterosaur jaws.

Pterosaur workers Mark Witton and Chris Bennett consider the curve-jawed specimen as being a normal condition for the animal, known from a beautiful specimen called the ‘Painten Pelican’. The current theory is that the strong, peg-toothed jaws grew more curved with age while the straight-jawed ones are still juveniles.

Others though, consider it to be a diseased individual and restore adults as normal, peg-toothed, thick-jawed animals without the contortion.

Whatever the case, it was a specialized animal, and it needed to be to coexist with many others of its kind.