The Lower Cretaceous Tugulu Group in northwestern China has yielded the disarticulated remains of at least 40 individuals of the pterosaur Hamipterus tianshanensis, as well as their eggs. Hamipterus was first named by Xiaolin Wang and colleagues in 2014 and is named for the Hami Basin and Tianshan Mountains.

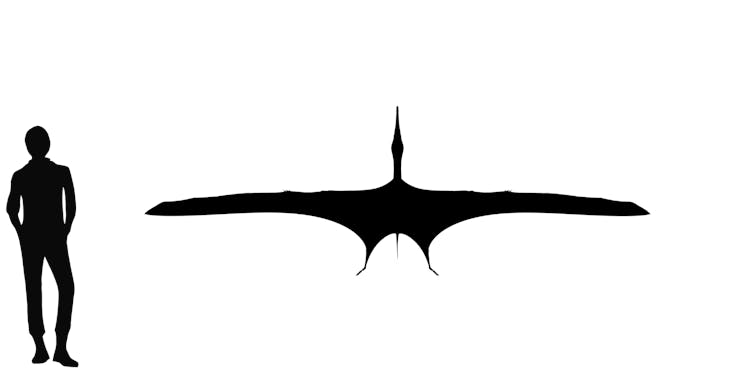

The skull of Hamipterus is quite long, narrow, and tapering, with expanded tips to the upper and lower jaws, similar to tongs. The top of the skull has a long, bony crest running from near the tip of the snout to the rear of the skull. The teeth are widely spaced and conical, and the tooth row extends for almost the whole length of the upper and lower jaws. The most complete specimens had skulls about 30 cm (12 inches) long. There are larger, but incomplete individuals that would have had skulls at least 40 cm (16 inches) long when complete. The remainder of the skeleton is entirely known, but briefly described. There’s a variety of sizes represented, with the largest individual having a wingspan of 3.5 m (11.5 feet).

There are two distinct crests types found in the bonebed. In the smaller type, the crest begins well after the 6th tooth position, and about doubles the height of snout. The larger crest type starts further forward, more than doubles the height of the snout, and has a leading edge that is quite tall and curls forward. Both crest types are decorated with vertically oriented, curving grooves and ridges running their entire length, but the decorations are more prominent in those with larger crests.

Wang and colleagues consider the variation in crest types to be indicative of sexual dimorphism, with the larger-crested individuals probably being males, and the smaller-crested individuals being females. They considered and discounted two alternative explanations for the different crest types, growth stages and individual variation. They noted that both crest types are seen in similarly sized individuals, so it’s unlikely the smaller crested individuals were younger. Additionally, there didn’t appear to be any individuals that had medium-sized crests, only larger and smaller, so it’s unlikely they represented variation within a population.

Incredibly, the location preserves five eggs among the skeletal remains. This constitutes the majority of known pterosaur eggs on Earth, as only four others are known from anywhere else in the world. The eggs are all about 6 cm (2.5 inches) long, and 2.5-3.0 cm (just over 1 inch) in diameter; about the same length as a chicken’s egg, but much skinnier. Like other pterosaurs and many other reptiles but unlike dinosaurs and birds, Hamipterus had eggs with a pliable, leathery shell.

Hamipterus is found in ancient lakebed deposits from the center of a tectonically formed valley. The specific layers where the bones were discovered are a type of sedimentary deposit known as a tempestite. Tempestites are very distinctive and are formed by mudslides associated with extremely heavy rains. Wang and colleagues proposed that the Hamipterus bonebed was formed when a nesting ground near the lakeshore (or possibly on a low island) was washed out by a mudslide. This mudslide killed dozens and possibly hundreds of individuals and washed away the nests.

When first described, Wang and colleagues found Hamipterus to be within the ornithocheiroid lineage, related to the boreopterids, istiodactylids, and ornithocheirids. All of these families had long snouts lined with teeth, and especially long and narrow wings. Hamipterus most resembles the ornithocheirids – ocean-going fishers like Ornithocheirus and Anhanguera – with respect to its conical teeth and narrow jaws with expanded, tong-like tips. Although Hamipterus lived well inland, it too was an aerial fisher, possibly fishing in the lake that would eventually entomb these skeletons.