Quetzalcoatlus

Family

Azhdarchidae

Family

Azhdarchidae

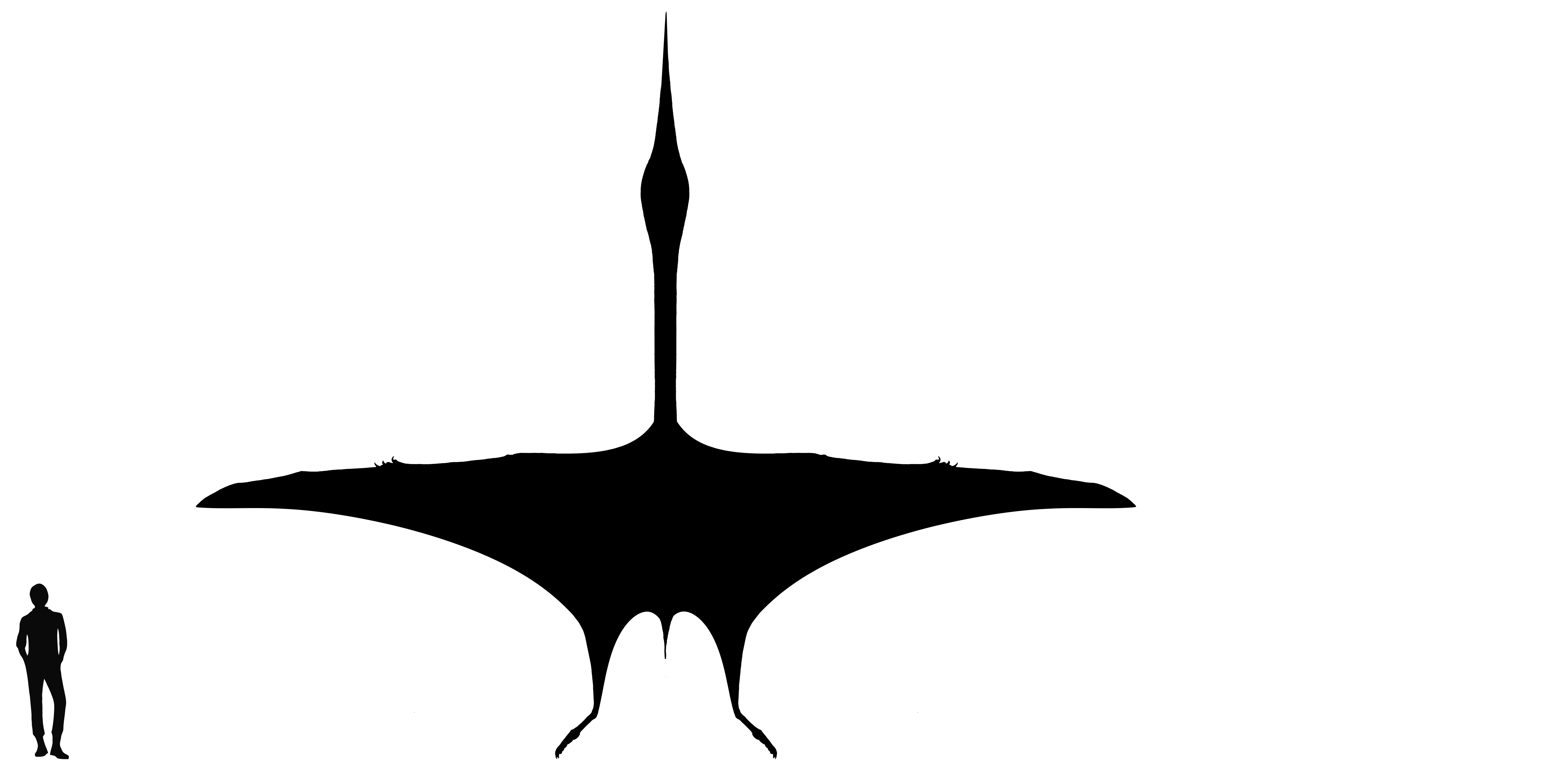

Quetzalcoatlus is often described as the largest pterosaur and the largest flying creature of all time. Despite its massive size and coexistence with Tyrannosaurus though, its biology has long eluded discovery.

The holotype, consisting of parts of an arm including the humerus and wing finger, was discovered in 1971 in the Maastrichtian-age Javelina Formation, part of the Big Bend National Park in Texas. The animal lived somewhere between 68 and 66 million years ago, perishing when the Mesozoic Era itself ended.

A year later, more finds of a similar, smaller animal were discovered, represented by many individuals. Preservation in the Javelina Formation favors smaller animals over larger, which are often fragmentary. The discoverer, Douglas Lawson, a geology graduate, named the larger animal Quetzalcoatlus northropi four years later. The majority of Quetzalcoatlus (Q. northropi and Q. sp.) fossils have been found inland, and mostly in the semiarid uplands of Texas.

The genus name is an allusion to the Mesoamerican serpent god Quetzalcoatl while the species name honors John Knudsen Northrop, founder of the Northrop tailless flying wing aircraft. The smaller animal was actually thought to be a separate species, and is forever known as Quetzalcoatlus sp., as classified by Alexander Kellner.

Q. sp. is much more complete than the massive type species, including much of the skull, and all Q. northropi restorations feature the head of Q. sp. to this day. The second species is also very much smaller than the first, with a wingspan of 5.5 meters. The larger one though, has had a rough time in popular literature. Some depictions showed it as being a monstrous vulture-like scavenger with a skinny, snaky neck, a pinhead and cloak-like wings.

This decidedly demonic-looking interpretation was abandoned in favor of something more slick, especially when acclaimed paleo artist John Sibbick did his restoration for David Norman's Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs.

At the time, it was still thought that Quetzalcoatlus either fished over freshwater systems or that it scavenged the carcasses of dinosaurs, its size assumed to be so great it could only soar (if it could even fly), or wander the fields, flightless.

Some estimates proposed its wings spanned 15 or even 20 meters, while weight estimates were ridiculously low. These could be less than 100 or even 70 kilograms while recently a maximum weight of 250 kilograms has been accepted for these giants. Recently, an estimate of a 10-meter wingspan inverted the older, ultra-light body but huge wingspan model for a heavier, narrower wingspan.

The animal may have stood erect, its body elevated upwards, and at over 5 meters, it would be as tall as a giraffe while on the ground, its beak allowing a sweeping view of the ground. This made it the tallest carnivore on its continent, towering over contemporary Tyrannosaurus itself, though the dinosaur was far more massive. The largest herbivore in the south was the titanic sauropod Alamosaurus, an animal that towered over even this giant pterosaur, roughly three times taller and 80 to 100 tonnes in weight.

Thanks to finds in Argentina, we know that sauropods probably flooded the environment with their precocious offspring by nesting en masse. With a high growth rate to maturity, taking just under 15 years to reach near-adult sizes, these baby sauropods may likely have made up a large proportion of the diets of the largest, and possibly both Quetzalcoatlus species.

Another pterosaur with a broader head has also been found in the Javelina Formation, but is as yet unnamed. Another possible species of Quetzalcoatlus is one from the Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota. Its wingspan is around 6 to 6.5 meters across.

Geological Age

Late Cretaceous

Environments

Lancian formations of North America

Locations

North America

10 m (33 ft)