Rhamphorhynchus

One of the best-known pterosaurs from the Late Jurassic, Rhamphorhynchus was also lumped together with its Solnhofen contemporary Pterodactylus as P. longicaudus in 1939. Before this it was part of the popular wastebasket taxon Ornithocephalus.

Finally it was reclassified in 1846 by Hermann von Meyer as Rhamphorhynchus muensteri in honor of fossil collector Georg Munster. The earliest species name included an umalut above the letter ‘u’ but according to the ICZN, which polices and manages the nomenclature of organisms, did not allow the use of any non-Latin letters in any organism’s binomial name. Aside from that, Rhamphorhynchus turned out to be the archetypal non-pterodactyloid pterosaur, giving its name to the entire group ‘Rhamphorhynchoidea’ which is now in disuse. Its family, the Rhamphorhynchidae is still in use. The fossils of these creatures are incredibly well-preserved, showing the wing membranes and the vane at the end of the tail.

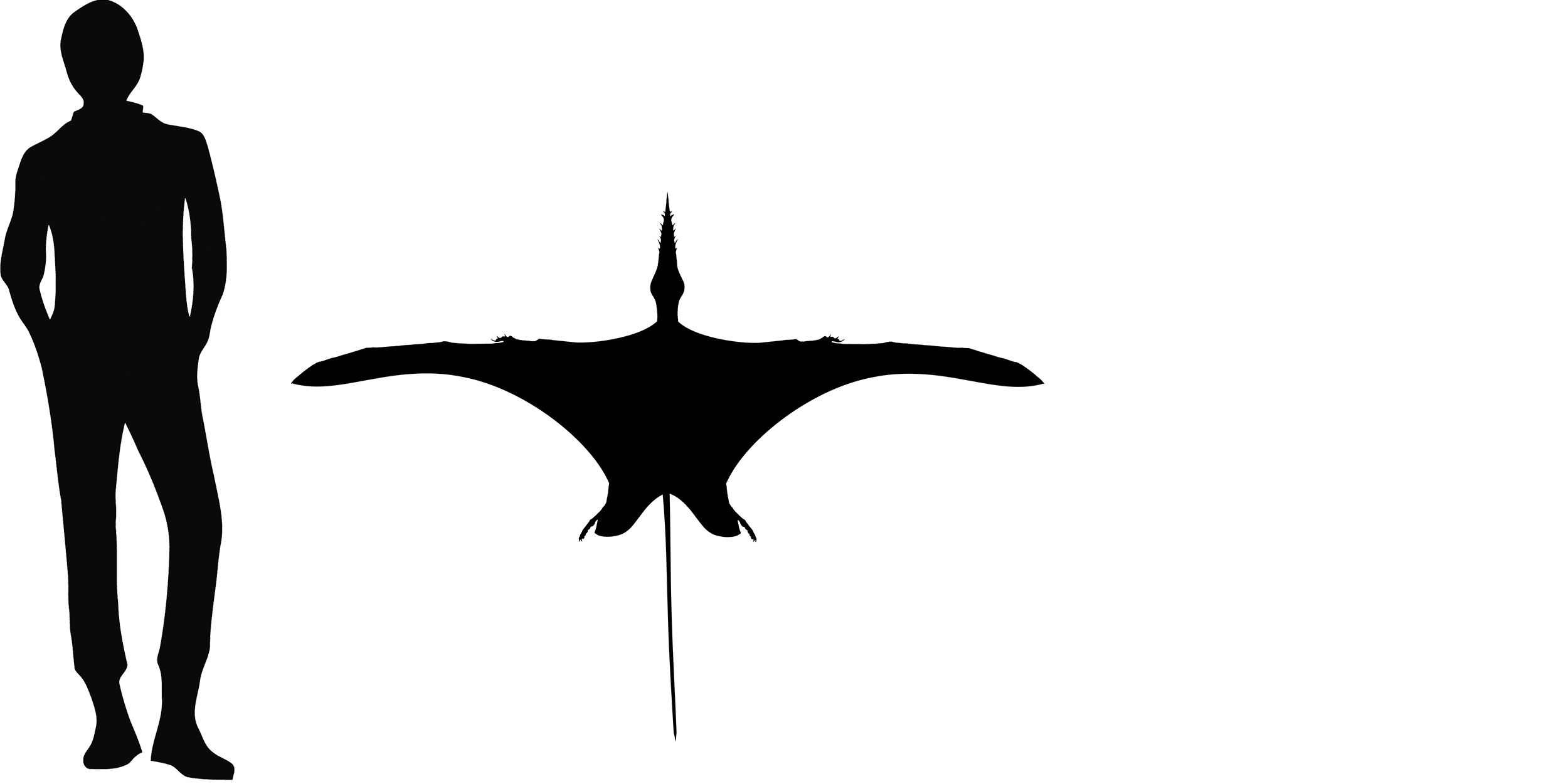

However, the genus did not have any kind of soft tissue crests, neither did it have a bony support for any kind of head integument. While small in comparison to the larger pterosaurs of the Cretaceous, Rhamphorhynchus is still among larger than most contemporary pterosaurs, and is the biggest one in its environment. Its wingspan is roughly 1.5 to 1.8 meters across and its wings are quite narrow. It was also a piscivore, with teeth that seemed to function as a fish trap for grabbing swift-moving prey from just below the waves. It was not, however, adapted for skimming as some have suggested in the past.

Evidence of its diet comes from a specimen with the small herring-like fish Leptolepides caught in its throat. It was also eaten by a number of other animals. For example, the same specimen had been caught in the jaws of the large fish Aspidorhynchus. This fish was a fast predator with the size and appearance of a pike. The struggle probably killed all of them, with the animals probably sinking down into an anoxic environment at the bottom of the lagoon.

Due to being known from incredibly preserved remains, a number of studies have been done on this animal. Some of the Solnhofen fossils include babies with 30-centimeter wingspans, as well as full-sized adults. Findings by Edina Prondavi have found an odd growth pattern in the creature. For one, the hatchlings were neither dependent on their parents nor were they free-flying, somewhat of a puzzling situation.

For many pterosaurs and animals in general, fast growth and early flight are not practical due to a need to properly allocate resources to fuel these processes. Both take up a lot of nutrients to work. Instead according to Prondavi's researcg the babies grew fast till they were more or less half the size of the adults. Afterwards, a period of slow growth occurred. The hatchlings grew up very fast. It is thought that they may have clambered around trees and bushes like a hoatzin chick.At this stage they might have fed on small arthropods and insects. They began flying at half adult size, far earlier than birds or bats which start flight at adult size. Studies of the animal also indicate that it may have been a nocturnal feeder.

1.8 m (5.9 ft)